Down Beat (p.69) - 3 stars out of 5 -- "[With] potent blues-rock...and Morrison's vocals still compellingly and haunting authoritative, the grip is relaxed..."

Rovi

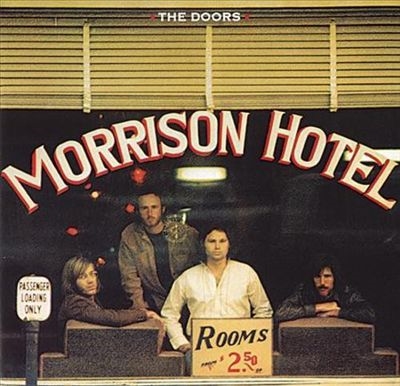

In late 1969, the Doors were reeling. That March, singer Jim Morrison was charged, tried, and convicted of obscenity for allegedly exposing himself at a concert in Miami. It resulted in promoters canceling future gigs. The July release of The Soft Parade provided more angst. Tired of the sound that governed their previous outings, the band incorporated horn and string arrangements with a new melodic accessibility. It signaled an unwelcome change for critics (though it did reach number six and was radically reappraised posthumously). In November they entered the studio with producer Paul Rothchild exhausted, stressed, and angry. Going back to blues and R&B basics seemed like the only direction to pursue.

Morrison Hotel is often dubbed the Doors blues album, due to raucous opener Roadhouse Blues, one of the bands most enduring tunes. (Interestingly, it was issued as the B-side of first single You Make Me Real.) Ray Manzarek leaves behind his organ to pound an upright piano, while guitarist Robby Krieger adds a filthy Chicago-styled riff, prodded by a rock shuffle from drummer John Densmore. The Lovin Spoonfuls John Sebastian (using the pseudonym G. Puglese) provides its iconic harmonica wail. Waiting for the Sun is one of four tunes Morrison composed himself, and a psychedelic holdover from the 1968 album bearing the same title. Manzarek plays a spacy harpsichord as Krieger offers trippy slide guitar. You Make Me Real underscores the blues-rock motif, with roiling electric piano, stinging guitar vamps, and Densmores swaggering shuffle. Morrison lords over all with his boozy, baritone roar. The organ returns on the downright funky boogie of Peace Frog, as Morrison sings of blood in the streets addressing the civic unrest then gripping the nation. He counters near the end with a spoken stanza from his optimistic poem Newborn Awakening. Ship of Fools contains shifting time signatures that cross jazz, R&B, and pop, while the buoyant Land Ho, offers an adventure-laden lyric in a sprawling rock & roll sea chanty, where Manzarek wields his organ like a mad calliope. Kriegers deep, bluesy, minor-key intro to The Spy is framed by jazzy electric piano and Morrisons sultry delivery, which approximates a lounge singer. Queen of the Highway is fueled by Densmores powerful drumming and Manzareks creative use of the Rhodes piano. One of the Doors most progressive cuts, it seamlessly integrates blues, jazz, and spacy psychedelia. Maggie McGill closes the circle on the blues tip. Kriegers unruly, double-tracked slide riffs duel with a pulsing, distorted organ; Densmore bridges them under Morrisons slithering growl -- it foreshadows the singing style he displayed so abundantly on L.A. Woman in 1971. Blues and R&B were foundational to the Doors musical vocabulary. They employed them to some degree on all of their albums, but never as consistently, adeptly, or provocatively as they did on Morrison Hotel, with absolutely stunning results. ~ Thom Jurek

Rovi

The Doors returned to crunching, straightforward hard rock on Morrison Hotel, an album that, despite yielding no major hit singles, returned them to critical favor with hip listeners. An increasingly bluesy flavor began to color the songwriting and arrangements, especially on the partynbooze anthem Roadhouse Blues. Airy mysticism was still present on Waiting for the Sun, Queen of the Highway, and Indian Summer; Ship of Fools and Land Ho! struck effective balances between the hard rock arrangements and the narrative reach of the lyrics. Peace Frog was the most political and controversial track, documenting the domestic unrest of late-60s America before unexpectedly segueing into the restful ballad Blue Sunday. The Spy, by contrast, was a slow blues that pointed to the direction that would fully blossom on L.A. Woman. ~ Richie Unterberger

Rovi